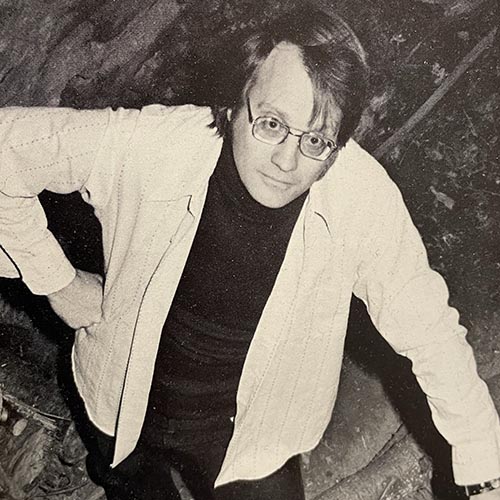

March 13, 1940 – April 6, 2023

The Coffeetown Grist Mill no longer looks like the windowless and roofless pile of rubble that Anne and Peter Beidler wandered around more than 50 years ago.

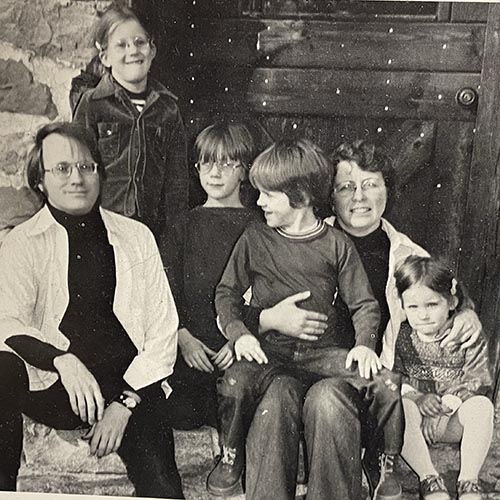

The newlyweds had driven to the Lehigh Valley so Peter could begin a graduate degree in English at Lehigh. They had their sights set on establishing themselves on a tract of property owned by Peter’s father, but upon their arrival, that plan fell through.

With nowhere to go, they found the dilapidated mill, fell in love with it, and plunked down their life savings of $3,000 to buy the property — money Anne had saved from teaching.

The mill, built in 1762, had no plumbing and no heat, a far cry from the refurbished site that now sits on the National Register of Historic Places.

It was a daunting project, a calling really, to refurbish and restore something of that scale — it required the mind of a person able to solve problems, create friendships with a range of people, and build something bigger and longer lasting than the individuals involved.

It typified just the type of projects that ultimately would define Peter’s life. With Anne by his side, together they rolled up their sleeves and got to work.

Early Lehigh

Beidler’s tenure in the English department began under the tutelage of J. Burke Severs, a notable Chaucer scholar. Beidler had never read Chaucer before taking Severs' required course. Beidler only signed up because he wanted “to get it out of the way.”

In a 2005 retirement story about Beidler published in the alumni Bulletin, he said upon opening the Canterbury Tales that “it’s not even in English. Not only will [the class] be boring, it’ll be impossibly difficult.” Soon he changed his tune, finding the stories to be “rich, varied, funny, touching, engaging, raunchy, philosophical, and psychologically complex.” He was hooked.

By 1964, he was working away at his dissertation on Chaucer. That’s when he met John Hirsh ’70, professor of English at Georgetown University (who sadly passed away in December 2023), on the top floor of Christmas-Saucon Hall. The two hit it off.

“Peter made things happen,” says Hirsh. “And was never stuck in a rut.”

That sense of wanderlust wasn’t always easy though. After Beidler defended his dissertation, he was offered a role at Lehigh. Rather than pounce, he paused, taking a year off to continue to fix up the mill and work as a project manager for an architect.

But what he was really doing was making a decision: Teach or not teach. Architecture and construction or academia.

“I’m not sure that it was the splendor of academics that won or that he saw the limits to being a carpenter,” says Hirsh. “While both were challenging, the greater intellectual challenge came from teaching and research.”

His commitment to teaching was unconventional: He never gave up teaching freshman composition.

“My father never described himself as a natural when it came to teaching,” says Kurt Beidler ’92.

Peter Beider himself described teaching as a “red-eye, sweaty-palm, sinking-stomach profession. Red eye because I never feel ready to teach, no matter how late I stay up the night before preparing for class. Sweaty palm because I’m always nervous before I walk into that classroom, sure that I will be found out this time. Sinking stomach because I walk out of the classroom an hour later convinced that I was even more stuttering and bumbling than usual.”

“He did have to work at it and plan it out,” says Kurt. “He was devoted to it and always prepared.”

“He learned a lot at Lehigh,” says Anne. “He gave a lot of himself there.”

He captured some of those learnings in his book Writing Matters, a collection of short essays he wrote and disseminated to first-year students to help them learn how to write. He introduced that book by saying, “Once upon a time, when I began my teaching career at Lehigh University, I had no idea how to teach writing.”

His colleagues tell a different story.

“He was charismatic,” says Barbara Traister, professor emerita of English. “He attracted students of all kinds from across the curriculum and was wonderfully suited as an undergraduate instructor. Students were mesmerized.”

“Pete was one of the most interesting and engaging individuals I have ever known,” says Joe Sterrett ’76 '78G '03P '05P '07P '09P, Murray H. Goodman Dean of Athletics. “He was an extraordinary teacher by all accounts — creative, innovative, energetic. He made learning fun and enduring, finding ways of combining traditional learning experiences with pragmatic applications.”

“He was dynamic and could take material very distant from students and make it feel very close to their lives,” says Scott Paul Gordon, Andrew W. Mellon Chair professor of English.

Traister envied him as a researcher as well. “He was an engaging and perceptive critic and was always looking for something new and different,” she says.

“He was a prolific scholar,” says Gordon.

“I used to say if you sneezed, that Peter Beidler could write an anecdote about it and get published,” says Traister.

Over his career, Beidler authored or co-authored 32 books, edited 11 book-length projects, and wrote 207 articles.

“He took pride in his teaching and his research,” says Kurt. “He valued both and was equally invested in both.”

“He wasn’t a big-picture guy impressed with his own grand arguments,” says Gordon. “He was much more particular, zeroed in on the nuts and bolts.”

A prime example of this is his book on the raft used in Mark Twain’s masterpiece Huckleberry Finn. Beidler figured out that the raft Tom and Finn used to float down the Mississippi River is a far cry from how it’s often depicted.

“His knowledge of wood and barge rafting made him totally confident in what he wrote,” says Kurt. “He went so far as to build a model.”

Putting the work into action is a career-long theme. Take his retirement. Rather than fade into the background, he retired by taking a group of high school English teachers on a trip to Canterbury, England, to better understand Chaucer and use the author’s works in class.

His approach is what gained him national attention when he decided to form a corporation with students, borrow money from a bank, purchase a run-down house, and fix it. All done over the course of a single semester. All while moving through a robust reading list of books on self-reliance.

Self-Reliance Inc.

CBS News. ABC News. “Good Morning America.” Time magazine. Seventeen magazine. All were descending on Bethlehem to tell the story of the Lehigh professor and students working on the fourth R: Reading, writing, ’rithmetic, and self-reliance.

He and his students secured a $10,000 loan in 1976 to purchase and repair 914 Vernon St. in Southside Bethlehem. While the process to approve the course, insure the students, find the right home to buy, and secure the funds from a bank was beyond daunting, it took just minutes to sign the loan.

When he left the loan office, Beidler thought to himself, according to his book on the class, “Here we are: an idealistic thirty-six-year-old English professor and fifteen grinning college kids, most of them not yet twenty, thinking they could succeed, with little more than enthusiasm and guts, at a project that most professional contractors would not touch.”

The students dove in, many learning which end of a hammer to hold. As with any project, there was tension, drama, moments of falling out, and falling in love. The students tore down walls, framed, built stairs, insulated, placed windows, spackled joints, hung siding, sealed cedar shingles, poured a patio, and all of the other stuff that a house would need to sell. All guided by Beidler.

At the same time, they read: Walden, Brave New World, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. They discussed themes. They journaled.

Given the publicity, Beidler ruminated on the project’s appeal — was this idea new? Even Beidler said no.

“I decided that it must be partly the rightness of the idea [...] As for the newness of it, I was not so sure. After all, vocational-technical schools had been in existence for a long time. But we were not that. We were a corporation, not just a class. I was not in the business of training professional carpenters, as the vo-tech people were, but of training students on other career tracks to have some self-reliance and self-confidence. And we were trying to combine the theoretical with the practical in ways the vo-tech class never did.”

Together they studied the human condition and lived it. They dabbled in blue-collar experiences while planning on white-collar careers.

Anne remembers those days and the stress of it all working out. Her insider perspective saw two sides, much like Peter did. “He was single minded about that project and all of his projects,” she says. “But you can’t always go by what Peter wrote. He understood he had to tell a story to an audience. He, like any of us, could write for what he hoped it was.”

The corporation did succeed. They finished the home and sold it at a profit. The group divided those profits among themselves. The students in the course went on to fulfilling lives and careers. Beidler also benefitted.

Teacher of the year

In 1983, Beidler was named the national Professor of the Year. The second recipient of the award, he was selected by the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) among 114 nominees. Often cited in the materials were the approaches Beidler took, like he did with Self-Reliance, that were unconventional.

An anonymous colleague said, “He characteristically reverses the normal procedure, teaching students how to teach themselves, developing his own texts, giving exams before class discussion of work, dealing with real problems.”

Part of the award was a cash prize. He also delivered a lecture on Chaucer in Washington, D.C., to a room full of students and scholars.

“I remember he was asked a very difficult question about middle English grammar,” says Hirsh. “He answered it wonderfully. He was smart but never played up his intelligence.”

Despite these novel approaches, he never repeated them outright. So there was no second house to refurbish and sell. It wasn’t his style. As Beidler said himself, I “had tasted the waters of Walden Pond. It was time to move on to other nectars.”

Part of this is tied to his upbringing. His father, a notable architect and anthropologist who apprenticed with Frank Lloyd Wright, worked around the world. So Beidler had a peripatetic upbringing as he lived in Iraq, Vietnam, India, and Egypt. The family didn’t fly to those exotic locales. Instead they opted for crew boats, not ocean liners.

Maybe it was close quarters with crew members, but Beidler was always a friend to the working man, maintaining many close relationships with the contractors who helped him with bigger tasks—like the rafters at the grist mill.

One considerable reinvention came as a result of his home at Coffeetown Grist Mill. As Anne was doing research on the deed, she discovered that the property was part of the Walking Purchase. The tie to Lenape land inspired Beidler to dive into Native American literature.

Some of the results were conventional, such as his scholarship on the works of Louise Erdrich.

Of course, some of those results also led to unconventional adventures. He moved his family to a Hopi Reservation in Arizona so he could take a crack at writing a novel.

Anne recognized that it was a controversial decision.

“Peter was bold and believed in good luck,” she says. But their youngest child was three; the older children attended school on the reservation where they would be beat up, have their watches stolen, and sometimes be totally invisible to others.

The solution? Build community.

The Beidlers put a basketball net up on a nearby telephone pole. It drew kids from nearby to play. Having books and puzzles out helped too.

Another reinvention: a Fulbright scholarship that meant moving to China. It came at a difficult moment for the Beidler family. Anne had been just released from treatment for alcoholism when Peter announced that he had received the grant. Kurt was in high school with a focus on his girlfriend and cross country team. They held a family meeting.

“I was feeling fragile and horrified about what my choices had done to my family,” says Anne. “I really counted on my children not to support our move overseas.”

She was shocked when they all agreed to go.

“When they all said yes, I also agreed,” she says. “It was a unifying and terrifying time for us. We were part of the first wave of American scholars welcomed into China. Only eight other Americans joined us. We relied on each other as a family and used the time to heal and grow.”

China also took on great significance for Beidler as a teacher. After winning the CASE award, Beidler published a short essay on “Why Do I Teach.” Reader’s Digest later picked it up and distributed it globally.

Why I teach

What Beidler didn’t know but found out while teaching in China: His essay was required reading for all Chinese students.

That essay soon became a book and captured refrains that drove Beidler as a teacher and scholar:

“I teach because I like the freedom to make my own mistakes, to learn my own lessons, to stimulate myself and my students.”

“I stay alive as a teacher only as long as I am learning.”

In the book, he mentions students. One is Vicky Weiss ’77G, his first graduate student and professor emerita, Oglethorpe University.

“When I arrived at Lehigh, the faculty of the English department was entirely male,” she says. “Did it matter to Pete that I was a young woman straight out of a small liberal arts college most had never heard of? Not a bit. I will say that as his first dissertation student, Pete was tough on me. While I was writing my thesis, I thought my middle name was ‘rewrite’ — as in ‘Vicky, rewrite … blah, blah, blah.’”

She continues, “That said, chapters were returned to me within a week — with usually two to three (sometimes four) typed pages of comments, corrections, questions. If my idea was a particularly good one, Pete’s immediate response was ‘Send it out.’ By the time my dissertation was complete, I had three articles already in print, seven interviews at MLA, and two job offers — oh, boy … how smart I am. Heck, no. It was Pete nudging that girl from little Lehigh. Why? He was simply an incredible teacher and the best editor I ever had.”

His impact kept students enrolled and, sometimes at their lowest moments, alive.

Miriamne Ara Krummel ’02G, professor of English and medieval studies at the University of Dayton, soldiered on as a doctoral student thanks to Beidler after she had packed up her things to depart South Mountain.

“He said we were going to get a bagel in order to say goodbye,” she says. “But instead, he brought me to Drown Hall to talk with department leaders and reschedule my exams, only after encouraging me to be tested for an undisclosed learning disability.”

It’s a story that’s hard for her to tell because of her career success, but she credits it to Beidler.

“I am so grateful for his role in my personal and professional life,” she says.

Colleagues from professional associations laud him.

“Pete was amazing, a contemporary renaissance man who was a noted scholar in several different fields,” says Connie A. Jacobs, professor emerita of English at San Juan College. Jacobs and Beidler often sat on the same panels at Native American literature conferences, collaborated on articles, and worked on Beidler’s third edition of the A Reader’s Guide to the Novels of Louise Erdrich.

“Pete was definitely our Big One,” says Milton D. Cox, founder and director emeritus, Original Lilly Conference on College Teaching.

He says, “One of Pete’s quotes in 1984 at his first presentation at the Lilly Conference was, ‘Learning ought to be like a blind date. It may be a dud. It may be a furtive kiss. It may be a flat tire — but it may be the Big One.’ For me, this blind date — meeting and getting to know Pete at the conference — was the Big One. Pete’s creative teaching, probing questions, and passionate stories about teaching have inspired Lilly Conference participants for over 40 years.”

Beidler created impact for thousands, often in small moments, whether being the first to greet new colleagues or invite them to his long-standing monthly poker game, staying longer in class to answer a question or meeting students and student athletes for office hours, or influencing peers in his areas of interest or inspiring teachers in China.

He was aware of his power as a teacher. He had written in his famous essay: “As a teacher I had both a decent salary, and the only kind of power worth having, the power to change lives.”

Scholarship through illness

While his life changed after retirement, retirement didn’t change him. When diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Beidler moved to the Pacific Northwest to be closer to three of his four children.

Once there, he relished the lives of his family — both children and grandchildren. He published widely. He continued to work with wood. He still went to conferences in his field but this time hid his shaking hand in the pocket of his pants. He kept up with his slightly off-color jokes. He jotted down every idea that could become an article.

His circle of interest actually expanded because of Parkinson’s. In typical nuts and bolts fashion, he dove in. He created community again — this time with a Parkinson’s support group. He published books on his journey with the illness. He created an annotated bibliography, reviewing 89 books written about the disease. Just like he did as a teacher, he memorized every name of the nurses he met.

“He was obsessed with all of his subjects, including Parkinson’s,” says Anne.

In other words, he followed his own advice, crafted over a lifetime of accomplishments:

“Good writers never stand still. They become bored with writing the same kind of thing all the time. They need to move on [...] You will find that writing is never an all-down-hill trip, and that usually you have to work hard to get anywhere. But you will be amazed at some of the roads you can travel and the destinations you can explore.”

Despite the twists and turns and travel, Lehigh remained an anchor.

“Lehigh always remained one of his greatest loves,” says Anne.