Launched in 2024 as the first University Research Center at Lehigh, the Center for Catastrophe Modeling and Resilience is an interdisciplinary home for researchers in the academic, business, public, and private sectors who use simulations to estimate the potential losses from catastrophic events.

While the work at this center is galvanizing ways to use data to inform preparations and responses to global catastrophes, Lehigh graduates have been pioneers in this field for years. Meet one leader who is bringing awareness, action, and change to this global opportunity.

Franck Vogel ’99

Biochemistry

Background

He grew up in Traenheim, a small village near Strasbourg, France, in a family of wine makers. His house was surrounded by vineyards. He had a farm with two large gardens, fruit trees, and a number of animals — rabbits, ducks, sheep, and horses.

His passion then was tennis. He started to play at the age of 6 and looked up to international stars Stefan Edberg and Pete Sampras. But his passions soon expanded to other areas. Because of his natural surroundings, he decided to study biology and chemistry before diving into biochemistry to learn the mechanisms of life.

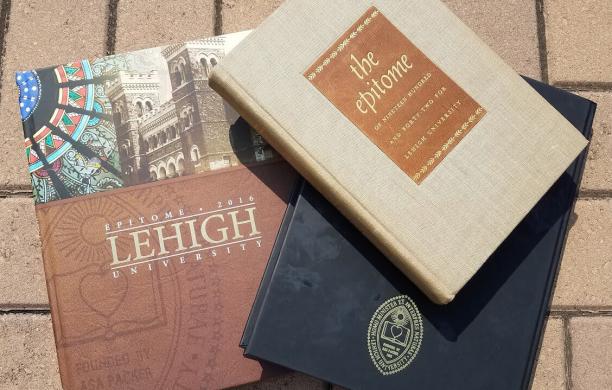

Lehigh Days

During his senior year at Louis Pasteur University in Strasbourg, Vogel wanted to discover the world and learn to speak English better, so he came to the United States and attended Lehigh via an exchange program. He studied biochemistry, virology, bacteriology, molecular biology, and was in the undergraduate research program, working with Michael J. Behe, professor of biochemistry. He was a member of the French Connection Club and had his first photographs published by FONI, an artistic magazine created by international students. Of course, he continued to play tennis and squash.

Upon his return to France, he was accepted into the best engineering schools for an advanced degree. He considered earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry with a focus on cancer research but decided instead to work and study, so he accepted a role at Accenture and completed courses for a master’s degree in business in 2001.

Work

He then quit. Vogel felt drawn to do something more, so he packed his bags and began to hitchhike around the world. Just him, his backpack, and his camera. Photography was a passion, but he didn’t consider himself a photojournalist.

His journey began in Nairobi. Based on his savings, he had about $3 a day for expenses. He could introduce himself in Swahili but had few other phrases at the ready. The gentleness, generosity, and goodness of people helped him thrive. He was invited into homes of strangers for meals, lodging, and conversations. Twice a month, he’d find an internet cafe where he could send family updates.

From this starting point, Vogel ventured to Kenya, Tanzania, and Rwanda over four months. Then he flew to Bombay and spent three and half months in India and Nepal. Then five and half months in Southeast Asia, venturing through Burma, Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia. He took more than 8,000 slides, mailing film back home.

Over this journey, he learned about his mission, role, and goals in life. A meditation exercise in the Himalayan mountains given to him by a monk helped him realize that he must find a way to blend travel, people, and photography in order to inspire action. He just wasn’t sure how he could do it.

Work Made Personal

Vogel returned to France and began to show his work. It soon led to a project with Hewlett Packard as it developed new photographic lamps and paper to display his work. Vogel then hit the road again, traveling to India to work with a people often considered the first ecologists: the Bishnoi.

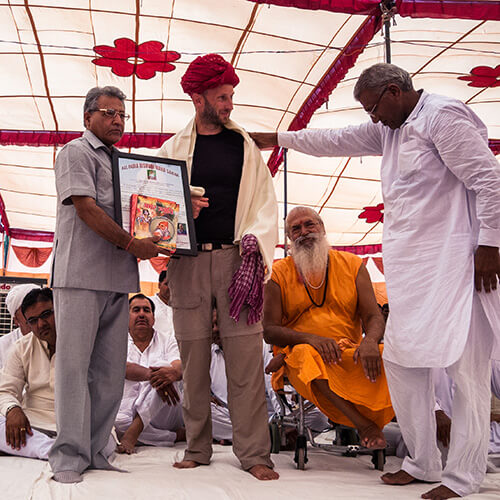

Since 1485, the Bishnoi have been living in harmony with animals and nature, following 29 principles that emphasize compassion, simplicity, and environmental conservation. Living in a climate that had no rain for a decade makes such principles take on a different gravity. Vogel built relationships and captured images that were published worldwide and led to exhibits, films, and speaking engagements.

Vogel has returned many times, living with them once for a year and a half. In 2013, he was made an ambassador for the Bishnoi people and received their highest honors.

This lifelong project allowed for more opportunities for him to share other stories of amazing people, like entrepreneurial women in Ghana making organic shea butter, Peruvian miners extracting gold in humane ways, and honey producers in Burkina Faso who have transformed their local economy.

He wants to highlight people willing to think differently and change their world by both doing good and still doing business.

Catastrophe Modeling

Over the last eight years, Vogel has focused his lens on increasing awareness of global water issues. He spends each year at a different major river, including the Nile, Mekong, and Ganges. In the U.S., it was the Colorado, the only river in the world that no longer flows through its delta to reach the sea.

He traced the waterway to better understand the issues that impact the seven states and the 27 million people who depend on it. The water flows into agricultural and leisure uses as well as households. But water rights from old agreements continue to win.

While many Americans are aware of the complex issues leading to the Colorado’s rapid demise and can point the blame at easy targets like golf courses or almond trees, Vogel found it was alfalfa crops in the Imperial Valley that did the most damage. If those growers altered their practices, Colorado River waters would reach the sea within six months.

“We can be very egotistical in our behaviors and often forget that we are not the masters of nature,” he says. “We are a part of nature, not separate. It can be hard to watch us sitting on a branch of a tree while we saw at the limb. It just takes one person with a vision planting the seeds of understanding so that we can see the changes that will work for all species.”

Finding and inspiring those visionaries is clearly Vogel’s mission.