Shared Mission

Shared Mission

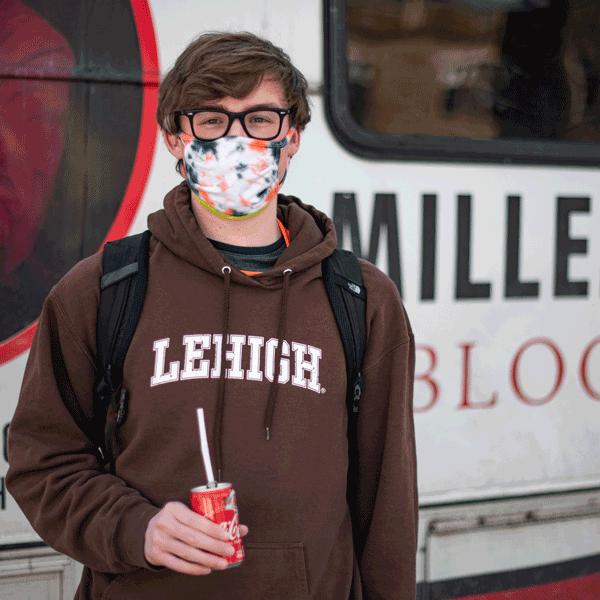

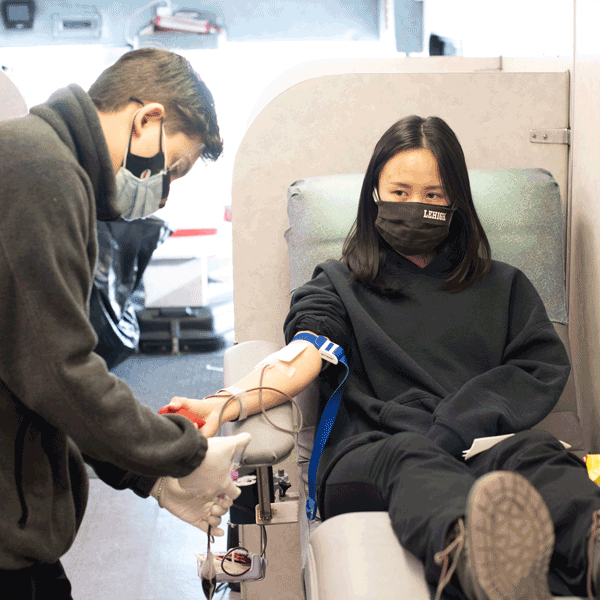

Since 2018, Lehigh University and Lafayette College have competed annually for the coveted Life Cup trophy, an honor given to the rival school that can recruit and collect the most donated units of lifesaving blood. After Lehigh beat Lafayette in the first year of the Rivalry blood drive, Lehigh reported that donations on campus increased by more than 65%. The 2023 Rivalry blood drive was held on April 24 at Miller Keystone Blood Centers (MKBC) in Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton.

Campus events across the country — such as the Lafayette/Lehigh Rivalry Blood Drive — have a significant impact on the national blood supply. According to the American Red Cross, high school and college students provide about 20% of blood donations, a large segment that impacts the overall numbers in a big way. Donations from other groups throughout the year close the gap left by students during the holiday and summer seasons, when shortages are most common due in part to colleges and high schools being out of session.

Donors Save Lives

Blood donors are essential to the U.S. healthcare system. Blood transfusions are given to patients in a wide range of circumstances, including serious injuries (such as in a car crash and burn victims), surgeries, childbirth, anemia, blood disorders, cancer treatments, and organ transplants.

Red blood cells have a short shelf life of 42 days, and there is no substitute for blood products. In 2021 and 2022, the blood crisis in the Lehigh Valley required local blood banks and hospitals to ration their supplies, and any incoming trauma threatened to deplete their supply. As detailed in the Morning Call in January 2023, the Lehigh Valley blood supply has regained some of its strength, but the supply is still below preferred levels.

Falling Short

Falling Short

The blood supply can't always meet the demand because only 38% of the U.S. population is eligible to donate blood, and only about 2% of eligible people donate blood each year, according to Cedars-Sinai. While blood of all types is needed, blood centers often run short of types O and B red blood cells. Type O negative cells can be given to patients of all blood types and therefore are the first line of defense in a traumatic event when time is critical. Only 7% of people in the U.S. are type O negative, so it’s always in great demand and often in short supply. According to GivingBlood.org, statistics show that if all current blood donors gave three times a year, blood shortages would be a rare event — the current average is about two.

Time Well Spent

Gehar Bitar ’20 is lead medical technologist of quality control for Miller-Keystone Blood Center. Bitar reinforces that while the supply has improved in 2023, donation rates took a significant hit during COVID-19 and have yet to recover. Any significant trauma or mass casualty can greatly impact a hospital’s blood supply. Bitar explains that hospitals usually house their own supply and are replenished each day from a blood center such as Miller Keystone or the American Red Cross. MKBC services over a dozen hospitals as their primary blood center, and if its supply is unable to fulfill orders, the hospital needs to try another center or wait until the next day.

Bitar, whose undergraduate degree is in biochemistry, says that though we might be able to improve the time it takes to get the blood from donor to hospital, she doesn't think we are close to finding something that can 100% replace blood transfusions on a cellular level. She says that if we want to ensure there will be blood available for everyone who needs it nationwide, we need donors from all groups to step up, but especially in the 20s and 30s age groups where the rates are lowest. As noted in USA Today, fewer than 10% of blood donations come from ages 23-29 and approximately 12% from those in their 30s.

“It does not take a long time to donate a unit of blood,” Bitar says. “You can save somebody's life. Especially if you are a rarer blood type, it will get used. […] You could save a baby!”